Survey on ecosystem services of urban floodplains in Madagascar

Constance Brouillet, a PhD Student at PLUS and member of the FCL Tana project, has just returned from Antananarivo (capital of Madagascar) after a successful survey campaign lasting almost two months. In this article, she outlines her experience.

On Friday, September 9th, I flew from Paris to Antananarivo. I was excited but also nervous and wondering what unknowns and experiences would come from the next months. I returned to Zurich nearly two months later, heavily packed with kilos of paper in my suitcases, a lot to reflect on, and a sense of accomplishment.

Week 1 - preparation, training & testing

Day 1 - Once I arrived in Antananarivo, it felt like I never left. I drove to la Maison du Pyla, a charming guesthouse and a lovely host at the foot of the University.

Work began Monday morning with a meeting at the university with the local coordinator of our project, Dr. Ntsiva Andriatsitohaina, and Nantenaina Ravoahangilalao, the masters student who helped supervise the survey campaign. We set up the program for the next two weeks (logistic, schedule, materials, contact with local institutions, etc). We then went to the city in the lively market of Analakely in order to get the necessary material for the interviews.

On Tuesday and Wednesday, I met with the four other students and recent graduates of the external page ESSA-Forêt department (École Supérieure des Sciences Agronomiques – Mention Foresterie et Environnement) who would be helping me in the coming weeks to collect the surveys. After an introduction to my research, the students role-played the survey participants, proposed adaptations, discussed the best way to ask questions, and agreed on a common translation from French to Malagasy of key terms.

Thursday was our first day in the field. Students tested the survey in groups of two. Afterwards, they exchanged the difficulties they had and how we could overcome them (e.g., fatigue on their part or the participant's part).

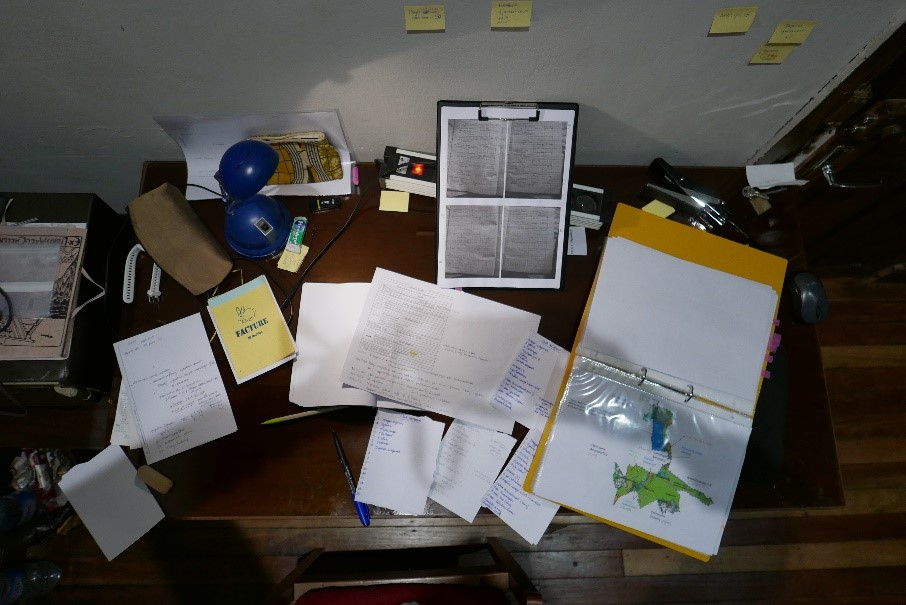

On Friday, students were free to familiarize themselves with the survey while we continued the preparation further. As always, what you don't anticipate is what causes the most problems... Printing 4,750 pages of surveys (19 pages times 250 surveys) and getting money to reward participants for their contributions was not an easy task. However, things are much more negotiable in Madagascar than in Switzerland (unsurprisingly) and we were able to find a solution.

Week 2 to 6 – survey campaign

The survey campaign officially started in the second week and lasted for four weeks. During this period, we visited 6 localities to cover different land-uses (wetlands, rice fields, market gardening areas, rivers, residential areas). The survey targeted direct users of floodplains in the peri-urban landscape of Tana (mainly farmers and brick-makers). It was designed to evaluate the key urban ecosystem services provided by these floodplains (food, flood regulation, supply of construction material, recreation & aesthetics of the landscape), to understand what kind of transformations are occurring in these landscapes and why, and to understand the impacts of climate change on practices and land-uses. In about four weeks, students were able to complete 263 surveys and met our goal. This success was not taken for granted since we had to face many difficulties and challenges: the weather, the insecurity, the traffic jams, the mistrust of people, etc.

One of the major challenges of the field campaign was to select and find participants who were eligible to complete the survey. There are few streets with names in Madagascar and little information about peoples’ professions. We therefore adapted our strategy according to the locality and the information we had available.

Another problem was security. While in some places we felt very welcome, in others we decided not to continue the survey campaign. Many participants were also suspicious of our presence, and especially of mine as a Vazaha (foreigner, white or tourist, in Malagasy), because they are victims of land grabbing by different actors for the construction of roads, industries and other urban projects. Despite this, the students were pleasantly surprised by the kindness and welcome of the participants and I witnessed many great laughs and nice encounters.

Another challenge we faced was the endless traffic jams between the city and the suburbs that forced us to adapt our daily schedule so that our drive would not be extended by 1 to 2 hours.

Week 7 to 8 – time to transfer the paper surveys into an electronic database

Once the fieldwork was completed, the next task was to transfer the paper surveys into an electronic database. It may seem archaic to still use paper in the 21st century but working in a peri-urban environment is not a safe place. Walking with tablets or smartphones can be dangerous so we decided to avoid an additional source of insecurity. Unfortunately for us, that week the JIRAMA (the state-owned electric utility and water services company) announced a widespread power cut for a few days throughout the city (without informing exactly which days and for how long!). Fortunately, this shortage did not last long, and the students were able to work on their tasks.

Finally, I would like to end this long post by thanking a few people who made this work possible. First of all, a big thank you to the students who have conducted these surveys with seriousness and the desire to learn. Thanks to Ntsiva and Nantenaina that did a remarkable job supervising and coordinating the project. I would also like to extend a warm thank you to the Fokontany of Vahilava, Ambihivy & Ambohimangidy who facilitated the study and opened their offices to us. Thanks also to the heads of the different associations for giving us access to their members. Finally, I would also like to thank Fanja for the delicious dinners at the Maison du Pyla and for making me feel at home.